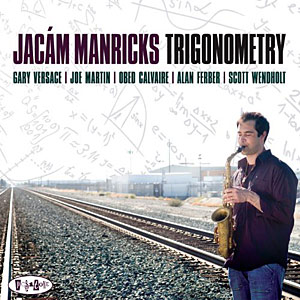

Track Listing: Trigonometry; Cluster Funk; Slippery; Nucleus; Miss Ann; Sketch; Mood Swing; Labyrinth; Combat; Micro Gravity.

Personnel: Jacám Manricks: saxophones; Gary Versace: piano; Joe Martin: bass; Obed Calvaire: drums; Alan Ferber: trombone; Scott Wendholt: trumpet.

Style: Modern Jazz

|

The reason that there is seldom a wrong note played by Jacám Manricks onTrigonometry is that notes, phrases and the spiraling flow of seemingly unending lines appear to be so extremely well thought-out that nothing could possibly sound out of place. To hear the saxophonist play in soft, dulcet tones that occupy the paler colors of a woodwinds player’s tonal palette is like listening to an apothecary conjuring up a mysterious aural recipe that will ultimately produce some magic potion. This, in turn will set the troubled mind right.

Manricks displays outstanding control over his breath, expelling it in long, warm gusts. His curved glissandi are soulfully suggested amid the rapid, ringlets of sound that favor his longer lines. There are also times when Manricks resorts to shorter, probing phrases, played in sharp stabs at scales made in surprising, complex rhythmic figures. His playing is bold, leaping into the musical unknown—experimenting, not only with sparingly used modes, but also with odd time signatures. His probing, pensive playing always characterizes what he does, whether he is making melodic leaps from register to register, or leading his ensemble by sharing a breathtaking tonal conception.

Three tracks—”Trigonometry,” the epigrammatic “Mood Swing,” and “Labyrinth”—are shining examples of Manicks’ playing and form a sort of triangular center-piece of this album. The first piece defines the mesmerizing mind behind every composition on this album—the purity and exactitude of intervals, beautifully offset by altered chords, augmented and diminished, making the poetics of each song exquisitely unpredictable. “Mood Swing” is a somewhat extended work that reveals the liquid emotional state of the artist who must constantly reinvent him or herself to keep the voice refreshed, while “Labyrinth,” is informed of the puckish sense of play at work in Manricks’ mind, even as he carves the air around his horns with thought-provoking artistry.

“Miss Ann” is a triumph as well. Manricks’ treatment of Eric Dolphy‘s fabled tribute is harmonically rich and, unlike, Dolphy’s strident rhythmic embrace, Manricks holds “Miss Ann” in a more tender swathe of melody and harmony, allowing only for little altered chords, to create the song’s symmetry with a little dissonance. The duo of bassist Joe Martin, and truly inventive drummer Obed Calvaire takes center stage here, as pianist Gary Versace does on “Mood Swing” and “Micro Gravity.” Manricks’ arrangements for a larger ensemble, that includes trombonist Alan Ferber and trumpeter, Scott Wendholt, on both “Cluster Funk” and “Nucleus,” shows the saxophonist to be a sensitive arranger as well, especially as he shows his penchant for earthy colors and timbre.

This is an intriguing, imaginative album and augurs well for future work from this talented musician.

David Ashkenazy/ Out With It (Posi-Tone): While the version “I Want You” here is an intense tour de force, David Ashkenazy and company jump right into action on this album with ad adventurous run through of Wayne Shorter’s “Children of the Night.” Covering Stephen Foster as well as Lennon/McCartney is further testament to an element of courage that permeates this entire effort. The inclusion of Beatles material lives up to its durability and flexibility as well as its mainstream fame, during instrumental arrangements develop their own character.

David Ashkenazy/ Out With It (Posi-Tone): While the version “I Want You” here is an intense tour de force, David Ashkenazy and company jump right into action on this album with ad adventurous run through of Wayne Shorter’s “Children of the Night.” Covering Stephen Foster as well as Lennon/McCartney is further testament to an element of courage that permeates this entire effort. The inclusion of Beatles material lives up to its durability and flexibility as well as its mainstream fame, during instrumental arrangements develop their own character.

Sarah Manning

Sarah Manning