Gathering a hand picked bunch of all stars to make the trek with him as he brings his sound and vision to fruition, Dease and his bunch make a history of jazz recording that has no dust on it and sounds much more looking forward than looking backward. A dazzling set that’s striking in it’s ability to say something new here, this is more than a pleasingly swinging set that cooks. A solid work throughout, this is thoughtful jazz that doesn’t hesitate to cut to the chase and make it’s point. Exactly what the doctor ordered for that afternoon when you want to be alone with some jazz and let it roll. Killer stuff.

Gathering a hand picked bunch of all stars to make the trek with him as he brings his sound and vision to fruition, Dease and his bunch make a history of jazz recording that has no dust on it and sounds much more looking forward than looking backward. A dazzling set that’s striking in it’s ability to say something new here, this is more than a pleasingly swinging set that cooks. A solid work throughout, this is thoughtful jazz that doesn’t hesitate to cut to the chase and make it’s point. Exactly what the doctor ordered for that afternoon when you want to be alone with some jazz and let it roll. Killer stuff.

Category: Reviews

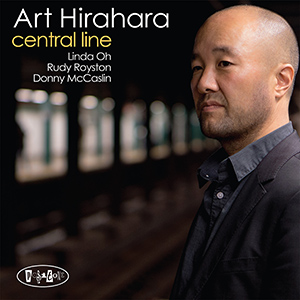

Midwest Record gives us a look at “Central Line” by Art Hirahara

Here’s a piano man bold enough to make a modern, mainstream date and doing it while surrounding himself with hell raisers like Donny McCaslin, Rudy Royston and Linda Oh. Swinging easy but to the left, you won’t mistake this

Here’s a piano man bold enough to make a modern, mainstream date and doing it while surrounding himself with hell raisers like Donny McCaslin, Rudy Royston and Linda Oh. Swinging easy but to the left, you won’t mistake this

for cocktail jazz but Hirahara could do a killer job on that form if he every chose to take the easy way out. Piano fans take note, this is a date not to be missed. Hot stuff.

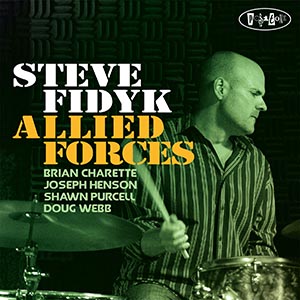

All About Jazz gives a great review for “Allied Forces” by Steve Fidyk

The military reference in this record’s title is right on the mark. For over a quarter of a century, Steve Fidyk has held down the drum chair in the U.S. Army Blues (part of the United States Army Band “Pershing’s Own”), an 18-piece ensemble that has performed America’s original art form in a variety of venues throughout the U.S. and around the world. Like any great jazz trapster, Fidyk plays the role of commander in chief—which is not to say that Allied Forces is a drum centric record. And speaking of commanders, check out the aphorism by General George S. Patton printed inside of the disc’s booklet, amid the backdrop of marching American troops.

The military reference in this record’s title is right on the mark. For over a quarter of a century, Steve Fidyk has held down the drum chair in the U.S. Army Blues (part of the United States Army Band “Pershing’s Own”), an 18-piece ensemble that has performed America’s original art form in a variety of venues throughout the U.S. and around the world. Like any great jazz trapster, Fidyk plays the role of commander in chief—which is not to say that Allied Forces is a drum centric record. And speaking of commanders, check out the aphorism by General George S. Patton printed inside of the disc’s booklet, amid the backdrop of marching American troops.

Fidyk excels at putting various components of the drum set in places that challenge his bandmates to dig deeper and thrive on their own terms. A keen sense of dynamics and good taste coexists with a penchant for assertively directing the action. He’s equally good at generating hard, no nonsense swing—in full flight, Fidyk often reminds me of Louis Hayes—by executing pointed accents around the set (“Gaffe”); creating a dense cloud of sound via the crashing of large cymbals (“Food Court Drifter”); contributing to a head by gradually and ingeniously adding rhythms without upsetting the applecart (“One For T.J.”); and studiously laying down straightforward time with a stick on a partially opened hi-hat (“Good Turns”). During the course of “Gaffe,” there’s an impressive range of emphasis in Fidyk’s comping amidst solos by alto saxophonist Joseph Henson, guitarist Shawn Purcell, and tenor saxophonist Doug Webb. The leader is constantly listening, reacting, and asserting himself without ever assuming a dominant posture.

In the case of Thelonious Monk‘s “Evidence” and Charlie Parker‘s “Moose The Mooche,” Fidyk’s drums impact the way we hear these classic jazz compositions. His snare and toms bob and weave around Monk’s melody, creating a skittish counterline before the arrangement shifts to a swinging bridge in three-four time. Playfully irreverent, Fidyk’s drumming adds another dimension to the fiendishly shifty tune. While Webb and Henson swing their way through the theme of “Moose,” Fidyk punches his bass drum at key points and adds a smack to the snare, briefly initiating an insistent, funk-like vibe that rapidly evolves into a straight-ahead jazz mode. The foundation of “High Five” (one of Fidyk’s six original compositions on the record), a densely-textured funk-infused line in five-four time, consists of a cymbal rhythm that sounds like a baby’s rattle, pitted against the insistent thwack of the kick and snare.

Fidyk’s drums certainly aren’t the only reason to spend time with Allied Forces. Everyone in the band, which includes organist Brian Charette, does his share of the heavy lifting. Nonetheless, if you’re looking for an example of how a contemporary jazz drummer directs a diverse, complex repertoire with imagination, flair, as well as a healthy respect for the tradition, give this record a listen.

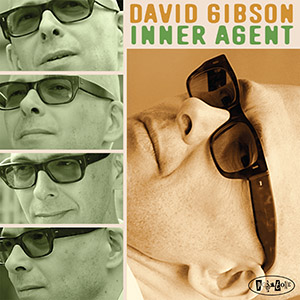

Why the World Needs More Folks Like David Gibson

If you follow trombonist David Gibson on Facebook, or are FB “friends” with him, you’re likely familiar with some of his posts that cover a whole host of topics, from the power of music, to what it means to be a professional, how to act on a gig, how to communicate with people you might not agree with, etc. In these posts he is always positive, insightful, and generally optimistic.

Now I tend to be pretty cynical and dark, and sometimes when I see one of his posts like this, especially if it’s early in the morning, I might let my “not only is the glass half empty, the glass is cracked” outlook get the best of me and start to write it off. But then I invariably find the grown-up part of my brain saying to me “dude, get over yourself, he’s right.” And then I think about what he said for a bit and move on with my day, often having found what he’s said to have some kind of resonance or significance with things I often think about or experience.

I cannot say I know Gibson, I’ve never seen him play, and I only know his music from his records. But based on my limited interaction with him online and knowing his music, I can say that the world needs more musicians, and people, like him. This is clearly evident on his newest album on Posi-tone: Inner Agent. It, along with his previous albums, exudes all the qualities that I’ve come to respect about him. It’s honest, positive, straightforward, swinging, hip (I mean just look at his fashion sense—I’m super envious of his suit collection), and there’s no b.s. or posturing. And it’s clear from the music that his bandmates—trumpeter Freddie Hendrix, pianist Theo Hill, bassist Alexander Claffy, and drummer Kush Abadey—appreciate and share these qualities as well. Simply put, Inner Agent is one of the finest straight ahead albums of the year and is as good as contemporary hard bop gets.

The album charges right out of the gate with the uptempo title track. Aside from Gibson and Hendrix’s burning solos, one of the most impressive aspects of the performance is the hookup between Hill and Abadey, who play off each behind the solos, pushing the soloists forward while filling gaps with jabs, fills, and well-placed accents. Hearing Gibson borrow a figure from one of Hill’s comped lines during his solo shows that these guys are locked in. And it would be a mistake to overlook Claffy, whose unwavering walking bass holds everything together. “I Wish I Knew” is so good, so soulful, and so full of optimism that it’s just about enough to restore my faith in humanity. The tune’s melody and easy swing could be straight out of a classic 50s or 60s Blue Note album. Gibson’s solo exudes a declarative joyfulness, Hendrix turns the heat up a notch with a few bluesy choruses, while Hill takes a direct and unadorned approach, using a series of single note lines. The quintet expands to a septet on “The Scythe” with the addition of tenor saxophonist Doug Webb and alto saxophonist Caleb Curtis. The four-horn front line adds power to Gibson’s tune, which features an angular bridge that ratchets up the tension. Webb wastes no time working up a lather, while Curtis and Gibson take a more measured approach. The tune is so well-suited for an open-ended blowing session I wish it had been twice as long to give the soloists more time to stretch out. “Gravy” is a medium, sly funk—it’s as if the band is in on a big secret, but we’re not quite hip enough to know what’s up.

The album charges right out of the gate with the uptempo title track. Aside from Gibson and Hendrix’s burning solos, one of the most impressive aspects of the performance is the hookup between Hill and Abadey, who play off each behind the solos, pushing the soloists forward while filling gaps with jabs, fills, and well-placed accents. Hearing Gibson borrow a figure from one of Hill’s comped lines during his solo shows that these guys are locked in. And it would be a mistake to overlook Claffy, whose unwavering walking bass holds everything together. “I Wish I Knew” is so good, so soulful, and so full of optimism that it’s just about enough to restore my faith in humanity. The tune’s melody and easy swing could be straight out of a classic 50s or 60s Blue Note album. Gibson’s solo exudes a declarative joyfulness, Hendrix turns the heat up a notch with a few bluesy choruses, while Hill takes a direct and unadorned approach, using a series of single note lines. The quintet expands to a septet on “The Scythe” with the addition of tenor saxophonist Doug Webb and alto saxophonist Caleb Curtis. The four-horn front line adds power to Gibson’s tune, which features an angular bridge that ratchets up the tension. Webb wastes no time working up a lather, while Curtis and Gibson take a more measured approach. The tune is so well-suited for an open-ended blowing session I wish it had been twice as long to give the soloists more time to stretch out. “Gravy” is a medium, sly funk—it’s as if the band is in on a big secret, but we’re not quite hip enough to know what’s up.

Like his last album entitled Boom!, Inner Agent closes with a cover of a pop tune. Whereas the former ended with Eric Clapton’s “Change the World,” he finishes the latter album off with George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun.” I admit that when I first saw that each of those were on the albums my inner cynic took hold and almost cringed. But then I thought “wait, ok, change the world, ok, things are pretty messed up, the world could use some changing.” And with “Here Comes the Sun”: “oh man, I’ve heard some bad Beatles covers, I hope this isn’t lame.” [*wrong, hits reset button*] “wait, this is hip, ok, ‘here comes the sun…it’s alright,’ we could use some sun and optimism and positivity.”

Perhaps it’s fitting that I’m finishing this review on the eve of the 2016 presidential election, which in all its ugliness, drama, immaturity, and divisiveness has made it painstakingly clear that for a great number of Americans, cynicism and exploiting people’s fears and base emotions remain effective tools for achieving one’s goals, whether they be profit, ratings, clicks, fame, or power. By listening to Inner Agent and following him online, David Gibson reminds me that music has the power to uplift and to share positive energy with all who encounter it, thereby helping to shed our cynicism. If only we’d listen.

A polished trio fronted by an articulate drummer is “Jazz Jukebox”

The predominance of the jukebox in social situations is essentially a thing of the past. But how much has really changed? Those once-ubiquitous machines that brought musical happiness to the good people in corner bars and diners throughout the land may have vanished, but the concept they put forward has not. It’s simply been modernized, with shuffling playlists, random streaming, curated listening parties, and smartly programmed albums like this now carrying the jukebox flame and furthering the mix-it-up musical formula.

The predominance of the jukebox in social situations is essentially a thing of the past. But how much has really changed? Those once-ubiquitous machines that brought musical happiness to the good people in corner bars and diners throughout the land may have vanished, but the concept they put forward has not. It’s simply been modernized, with shuffling playlists, random streaming, curated listening parties, and smartly programmed albums like this now carrying the jukebox flame and furthering the mix-it-up musical formula.

Jazz Jukebox is exactly what you’d expect, both based on the title and what drummer Jordan Young cooked up on his first two albums—Jordan Young Group (Self Produced, 2010) and Cymbal Melodies (Posi-Tone, 2012). It’s a diverse program built on sharp and concise arrangements of jazz and pop nuggets. Everything from Thelonious Monk‘s “Rhythm-A-Ning” to Jim Croce’s “Time In A Bottle” and Hugh Masekela‘s “Son Of Ice Bag” to Charles Ira Fox’s campy “Love Boat” makes it into the mix, and nothing overstays its welcome. The longest tracks don’t even crack the four-and-a-half minute mark.

Young keeps things moving here, largely focusing on upbeat material pulled from different corners of the music world. He nods to Larry Young with a performance of the organist’s jaunty “Paris Eyes,” gets his sloshy hi-hat going for a spell on The Beatles’ “I’m Only Sleeping,” prods organist Brian Charette and guitarist Matt Chertkoff during their solos on Wayne Shorter‘s “ESP,” and trades with glee on “Tadd’s Delight.” If that’s not enough variety, there’s also Charette’s “Giant Deconstruction,” an odd-metered, ascending twist on John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps”; Jimmy Smith’s soulful and bluesy “Eight Counts For Rita,” one of four numbers to bring tenor saxophonist Nick Hempton into play; and Chertkoff’s arrangement of “Will You Still Be Mine,” a caffeinated brush feature for the leader.

In choosing to work with Charette and Chertkoff, Young capitalizes on musical relationships that have been fostered over a long stretch of time—basically week in, week out at Tribeca’s Authentic Bar B Flat and other New York haunts. Due to those bandstand-forged connections, this crew is incredibly comfortable in its own skin. That’s something that tends to cut both ways. On the positive side, it makes for a strong team mindset in the music. All the stops, turns, and hits are incredibly tight. The group chemistry also fuels solid groove expressions—swinging, samba-esque, and soulful at different turns—which carry the music forward. The downside with the musical amity between these men is that it sometimes leaves the music wanting for more heat and/or friction. The band occasionally feels too comfortable. But is that really a problem? For most listeners, probably not. Those who dig the idea of sundry selections served up by a bright and polished trio fronted by an articulate drummer will be happy as can be when spinning Jordan Young’s Jazz Jukebox.

Dan Bilawsky – All About Jazz

All About Jazz likes what it hears on “Bright Side” by Doug Webb

From one perspective, Doug Webb‘s Bright Side is basically twelve tracks clothed in very recognizable forms —a few varieties of soul-jazz, a couple of heartfelt ballads, a taut bossa nova, and an array of middling and up tempo straight- ahead swingers. Although the material is thoroughly enjoyable, it’s tempting to succumb to a nagging notion that its all been done countless times before, and then simply move on to a record by yet another brave soul planting his/her flag in the jazz tradition. Fortunately, what enables Bright Side to add up to something more than a competent, professionally executed jazz record, is a slew of highlights, bright moments, and outright cool stuff that populates every track.

From one perspective, Doug Webb‘s Bright Side is basically twelve tracks clothed in very recognizable forms —a few varieties of soul-jazz, a couple of heartfelt ballads, a taut bossa nova, and an array of middling and up tempo straight- ahead swingers. Although the material is thoroughly enjoyable, it’s tempting to succumb to a nagging notion that its all been done countless times before, and then simply move on to a record by yet another brave soul planting his/her flag in the jazz tradition. Fortunately, what enables Bright Side to add up to something more than a competent, professionally executed jazz record, is a slew of highlights, bright moments, and outright cool stuff that populates every track.

A quintet consisting of Webb’s tenor sax, trumpeter Joe Magnarelli, guitarist Ed Cherry, organist Brian Charette, and drummer Steve Fidyk (all of whom have led dates for the Posi-Tone Records label) operates like a well-oiled machine. Listening to how nicely all of the parts fit together, and the fact that you can easily discern each player’s contribution, are important facets of the disc’s appeal. For instance, Cherry’s work on the heads and his comping behind individual soloists are delivered in subtle yet decisive ways that add rich, distinctive flavors—while taking up a minimum amount of space. The same can be said about Charette, whose primary concern is holding down the band’s bottom, but, with due cause, asserts himself by means of vivid chords. Fully capable of inhabiting any role the music requires, Fidyk often jolts the band with thickset snare accents, frequently plays fluid, inconspicuous jazz time, and always executes smart, stimulating fills regardless of the type of groove.

Webb’s voice as an improviser possesses real character regardless of the kind of song he’s playing. Check out the R & B influenced “Society Al” for the way in which he gets down by himself at the onset of the track, pausing and briefly falling silent amidst a fair amount honking and shouting. Later on during his solo over the band’s uncluttered funk, Webb executes notey runs, brief, tantalizing hesitations, quick, meaningful digressions, as well as broad, weighty tones—and makes all of them sound like they belong in close proximity to one another. Magnarelli’s solos—particularly on “Steak Sauce,” “Slo Mo,” and “Lunar”— contain a fair measure of brassy power mixed with a kind of subdued, floating quality that feels emotionally vulnerable. Cherry possesses a unique, understated style, doling out notes with a soulful circumspection. His all-too-brief intro to “One For Hank” is the epitome of sparse perfection, so simple that it’s easy to take it for granted. The guitarist’s gift for making improvised lines sound both ephemeral and sturdy is also apparent throughout the gentle “Bahia,” where every single note and chord breathes easy and carries an almost imperceptible weight.

In the end, Webb and company make it simple to enjoy the music instead of indulging in critical hair splitting or fretting about stylistic proclivities and influences.

David A. Orthmann – All About Jazz

All About Jazz gives “Message In Motion” 5 stars

Message In Motion is a recording that can be gainfully approached from a number of angles. You can choose to play it in a single sitting from start to finish, taking in an array of moods evoked by bassist Peter Brendler’s seven compositions and a band worthy of his exemplary skills as a writer. (The record also includes selections penned by Duke Ellington, Elliott Smith, and Alice Coltrane.)

Message In Motion is a recording that can be gainfully approached from a number of angles. You can choose to play it in a single sitting from start to finish, taking in an array of moods evoked by bassist Peter Brendler’s seven compositions and a band worthy of his exemplary skills as a writer. (The record also includes selections penned by Duke Ellington, Elliott Smith, and Alice Coltrane.)

Equally satisfying is the practice of detaching the compositions from the improvisations that follow, enabling one to focus on the care Brendler takes in crafting melodies, appreciate the shapes and contours of individual songs, as well as his shrewd employment of different configurations of a five-piece group. It’s easy to become fixated on each of his works, and after a while, despite their differences, they loosely cohere into some sort of aggregate. “Splayed” opens in a wistful manner that includes brief silences, and quickly turns harder and somewhat sinister. “Stunts and Twists” is a haunting, quasi-ballad that evolves in a long, restless sweep. Bearing the influence of the early work of Ornette Coleman, the densely swinging “Very Light and Very Sweet” seems to feed on itself. The deliberately paced “Gimmie The Numbers” makes bedfellows of elements ranging from gospel to gutbucket. Fueled by a firestorm of distorted guitar noise and punchy, drum dominated time, “Lucky In Astoria” sounds like a waltz on steroids.

Another rewarding course is concentrating on the work of each of the primary soloists—tenor saxophonist Rich Perry, trumpeter Peter Evans, guitarist Ben Monder, and Brendler—and making note of the ways in which the bassist and drummer Vinnie Sperrazza support and interact with them. As his tone declares a slightly sour disposition, Perry’s “Didn’t Do Nothing” solo sounds as if he’s pushing away some sort of obstacle without using a whole lot of force or emphasis, as if the effort is distasteful or futile to begin with. In general, his improvising is slippery, evasive, and—miraculously—right down the center of the music’s core. Throughout Evans’ wildly ambitious improvisations on “Splayed,” “Stunts and Twists,” and “Didn’t Do Nothing,” each note seems to be gobbled up by the next one, offering the impression of something being torn down and reassembled in a different form, all in one maniacal, continuous motion. Taking his cue from the song’s melody, during “Gimmie The Numbers,” Monder begins in a simple, direct manner, and eventually turns prickly, making darting leaps across the beat. During the incendiary “Lucky In Astoria,” his overwrought guitar and Perry’s tenor extemporize at the same time, as if they’re both trying to force their way out of a confined space by vastly different means.

It’s entirely possible that there’s no end to the discoveries and pleasures engendered by

Message In Motion. The music always encourages yet another listen. Highly recommended.

– All About Jazz

Musicalmemoirs’s likes the no nonsense straight ahead jazz from David Gibson

I have to begin this review by complimenting Positone Records. Every CD this company has sent to me reflects a high quality of jazz artists. It’s been a joy listening to each and every one of them. David Gibson is no exception to this course of excellence. “Inner Agent”, the title tune, is an original composition by Gibson and sets the mood for this entire project. It’s Straight Ahead, no nonsense jazz, just the way this reviewer likes it. Using a quartet of horns to thicken the musical brew, Gibson graciously shares his stage with a group of seasoned musicians. He lets each one solo and sparkle like jazzy jewels. Hendrix is compelling on trumpet, drawing the listener in with big bold tones and dynamic technique. Doug Webb always brings tenor madness to the studio, playing from the heart and Caleb Curtis on alto is a saxophone force to be enjoyed and celebrated. This is my first time hearing Theo Hill on piano and he’s impressive, innovative and skilled, knowing just how to comp and support the artist, then stretching out with solos that make you pay attention. Abadey on drums is powerful and relentless, giving this band the push and rhythmic inspiration they need to spiral up and over his percussive chops. However, it is Gibson’s trombone voice that bathes in the glow of a singular spotlight. They say that trombone is the closest instrument to human vocals and Gibson sings with emotional dexterity and polished technique. He’s an accomplished composer as well as a musician and offers four original tunes on this project. One is “The Scythe”, a high-powered, Be Bop tune that burns with fiery energy with Gibson’s solo floating solidly atop the rhythm section. You can hear Abadey’s drums throughout, egging the band on like a matador’s cape in front of an angry bull. I love the mix on this recording. Bassist, Alexander Claffy, has written “AJ”, a moderate tempo ballad that allows Gibson to set the melodic theme along with his horn section, sometimes harmonically but mostly in unison. If I were to have any criticism, it would be that Gibson’s improvisational solos are way too short. Gibson tackles two compositions by my Detroit home-boy, trombonist Curtis Fuller; “The Court” and “Sweetness”, where he shows admirable technique and self-expression. This is an album of music to be treasured in any collection. Perhaps Curtis Fuller said it best when he gave Gibson this dynamic compliment:

I have to begin this review by complimenting Positone Records. Every CD this company has sent to me reflects a high quality of jazz artists. It’s been a joy listening to each and every one of them. David Gibson is no exception to this course of excellence. “Inner Agent”, the title tune, is an original composition by Gibson and sets the mood for this entire project. It’s Straight Ahead, no nonsense jazz, just the way this reviewer likes it. Using a quartet of horns to thicken the musical brew, Gibson graciously shares his stage with a group of seasoned musicians. He lets each one solo and sparkle like jazzy jewels. Hendrix is compelling on trumpet, drawing the listener in with big bold tones and dynamic technique. Doug Webb always brings tenor madness to the studio, playing from the heart and Caleb Curtis on alto is a saxophone force to be enjoyed and celebrated. This is my first time hearing Theo Hill on piano and he’s impressive, innovative and skilled, knowing just how to comp and support the artist, then stretching out with solos that make you pay attention. Abadey on drums is powerful and relentless, giving this band the push and rhythmic inspiration they need to spiral up and over his percussive chops. However, it is Gibson’s trombone voice that bathes in the glow of a singular spotlight. They say that trombone is the closest instrument to human vocals and Gibson sings with emotional dexterity and polished technique. He’s an accomplished composer as well as a musician and offers four original tunes on this project. One is “The Scythe”, a high-powered, Be Bop tune that burns with fiery energy with Gibson’s solo floating solidly atop the rhythm section. You can hear Abadey’s drums throughout, egging the band on like a matador’s cape in front of an angry bull. I love the mix on this recording. Bassist, Alexander Claffy, has written “AJ”, a moderate tempo ballad that allows Gibson to set the melodic theme along with his horn section, sometimes harmonically but mostly in unison. If I were to have any criticism, it would be that Gibson’s improvisational solos are way too short. Gibson tackles two compositions by my Detroit home-boy, trombonist Curtis Fuller; “The Court” and “Sweetness”, where he shows admirable technique and self-expression. This is an album of music to be treasured in any collection. Perhaps Curtis Fuller said it best when he gave Gibson this dynamic compliment:

“Out of all the young players I hear in the music today, David is one of very few who speaks the language of jazz.”

Classicalite says Peter Brendler’s “Message In Motion” lives up to it’s name

Another winner from the left coast’s Posi-Tone: consider it a Message In Motion by Peter Brendler where six of the tracks feature no chords whatsoever as it’s Brendler’s bass augmented by Rich Perry’s tenor sax, the trumpet of Peter Evans and Vinnie Sperazza with the type of kinetic drumming that continually moves the music forward.

Another winner from the left coast’s Posi-Tone: consider it a Message In Motion by Peter Brendler where six of the tracks feature no chords whatsoever as it’s Brendler’s bass augmented by Rich Perry’s tenor sax, the trumpet of Peter Evans and Vinnie Sperazza with the type of kinetic drumming that continually moves the music forward.

Brendler wrote eight of 10 and his compositional style gives everyone ample room to move. His two covers are “Ptah The El Daoud” by pianist Alice Coltrane [1937-2007] who was even more way out half the time than her icon husband John, and a real oddball pick of “Easy Way Out” by singer/songwriter Elliott Smith [1969-2003].

Four tracks have guest guitarist Ben Monder to add a few chords and a few runs of his own. Monder’s a monster. His Amorphae last year featured tracks with legendary drummer Paul Motian [1931-2011] from a scrapped 2010 duet project.

The sound is straight-ahead, exciting and constantly kinetic: it moves, man! Like the title implies, motion is inherent in these grooves. Continuing with the premise of his 2014 sophomore effort, Outside The Line, it expands the territory Brendler first sought out on his debut 2013 duo CD (The Angle Below, on Steeplechase Records) with guitarist John Abercrombie. Originally from Baltimore, Brendler graduated from Berklee in Boston before moving to New York City where he earned his Masters at the Manhattan School of Music.

Produced by Marc Free, engineered by Nick O’Toole, recorded at Acoustic in Brooklyn, mixed’n’mastered at Woodland Studio in Lake Oswego, Oregon, highlights include “Very Light And Very Sweet” (which lives up to its name, and you can hear sax man Perry’s transcribed solo below), opener “Splayed,” “Stunts And Twists” (syncopated and surprising) and, my favorite, the closing “Stop Gap.”

Mike Greenblatt – Classicalite.com

Jazz da Gama tells us how Behn Gillece cuts to the quick on “Dare To Be”

It takes but one ‘third’ to recognise the ‘hand’ of Art Tatum in ‘Willow Weep for Me’, a ‘flatted fifth’ to pick out Charlie Parker in any orchestral line up, a ‘seventh’ to do the same with Milt Jackson and while it may take a little while to pick out Behn Gillece from a flurry of notes, his vivid harmonic approach to the vibraphone is fast becoming his indelible signature, quite apart from the other two-handed vibraphone players out there as he cuts to the quick with every new song he performs.

It takes but one ‘third’ to recognise the ‘hand’ of Art Tatum in ‘Willow Weep for Me’, a ‘flatted fifth’ to pick out Charlie Parker in any orchestral line up, a ‘seventh’ to do the same with Milt Jackson and while it may take a little while to pick out Behn Gillece from a flurry of notes, his vivid harmonic approach to the vibraphone is fast becoming his indelible signature, quite apart from the other two-handed vibraphone players out there as he cuts to the quick with every new song he performs.

Dare to Be is the record that puts Gillece in a maze of mirrors in which reflections of past masters of the vibraphone can confound a young player of an instrument glorified by the likes of Red Norvo, Milt Jackson and Bobby Hutcherson. But certainly on this album, Behn Gillece breaks out. His ethereally resonant notes sound more knowing as the music on the album progresses. The positive surges of melody leap from a performance that juxtaposes utmost delicacy with eruptive power. Similar mastery of contrast makes Gillece’s account of a blues quite memorable and affecting. His playing is intensely alive to expressive nuance, textural clarity and elastic shaping, and his sound maintains a glow even at the most torrential moments.

Gillece has assembled a stellar group ion this rite of passage. Chief among them is Ugonna Okegwo, a bassist who, along with Jason Tiemann Nate Radley and Bruce Harris, provides the musical luminosity, spaciousness and zest from which Gillece’s fertile imagination takes flight. Ten graceful episodes fill this performance. Each is a gleaming gem, from the lilting melancholy of ‘Amethyst’ to the graceful spaciousness of ‘Dare to Be’ and the daring-do of ‘Trapezoid’ and the lilting buoyancy of ‘A Time for Love’. But no matter how virtuosic a performer you might be let’s be clear: you don’t adopt Jazz. The Music adopts you and it now eminently clear that it has taken Gillece under its wing.

Raul da Gama – JazzdaGama